When I was a 28-year-old teacher, my school's faculty voted against pledging the flag with the rest of the country on the one month anniversary of 9/11. It was a sign of things to come.

I didn’t know it at the time but a vote taken during a faculty meeting at Wellesley High School just days before the one month anniversary of 9/11 was a harbinger of things to come. I was a 28-year-old teacher at the time and while I was appalled by what transpired during the meeting, I had no idea that so many of the opinions expressed would come to be the norm when I had children of my own in school.

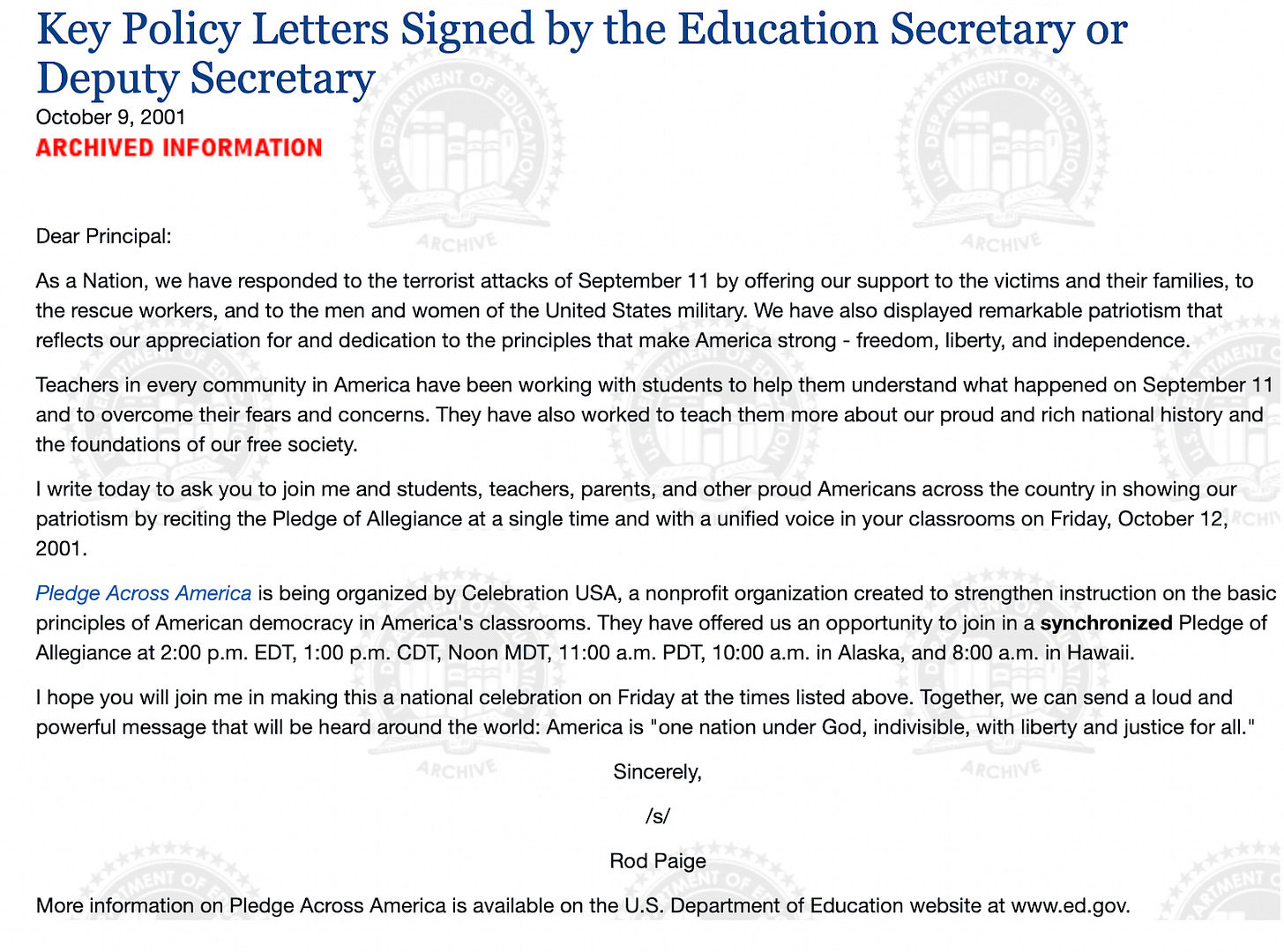

Some may remember that on the one month anniversary of the attack on our nation, K12 schools all over the country stopped what they were doing to pledge allegiance to the American flag at the same time—2pm on the east coast and 11am on the west coast. They did this because the secretary of education at the time, Rod Paige, had requested it in a letter sent to every single school principal in the country.

At most schools, this went off without a hitch and local and national news that night were blanketed with images and video footage of elementary, middle and high schoolers all over the nation reciting the pledge of allegiance at precisely the same time.

But not at Wellesley High School.

During our monthly faculty meeting, which happened to be just a day or two before the national flag pledging event, the principal matter-of-factly informed us of the secretary of education’s request and indicated that we’d participate.

And then all hell broke loose.

Hands went up as teachers began to object to the idea of participating in the “Pledge Across America” and while some of us in the room felt shock and incomprehension over the objections, most of us kept it to ourselves, partly because we couldn’t believe what was unfolding before our eyes. I remember thinking, “is this really happening right now,” as I sat there listening to colleagues, some of whom I loved and considered friends, arguing against pledging the flag with every other school in the country on the one month anniversary of the worst terrorist attack our country had ever faced.

Keep in mind, our participation as a school didn’t mean that every single teacher and student would have to recite the pledge. It did mean that we, as a school, would be part of this national showing of unity on October 11th. And somehow, that was unpalatable to a lot of people in the room.

One department head announced that because she was from Mexico, nobody should participate. Another brought up the prejudice she had faced four decades ago in school because she was Jewish. Others objected because they had family members or friends or students who, in their opinion, did not experience “liberty and justice for all” living in America. Others said it felt like “McCarthyism” and “jingoism.”

One remark I found a bit flippant was “what do we lose by not doing it?” The person who said it then went on to conclude that we lose “nothing” by not doing it so why do it?

One veteran faculty member who had served in Vietnam and always stood “at attention” when the national anthem was played, surprised many of us when he spoke out in opposition to participating—but his argument was different. He opposed making people who were hostile to the idea participate because it was a sign of disrespect to the flag and that didn’t sit right with him. His opinion seemed to be, if we aren’t going to do it right, let’s not do it.

It was obvious that the principal had been completely blindsided by the barrage of objections to her announcement and right or wrong, she made a split second decision to put it to a vote.

The majority of the faculty in attendance at the meeting voted against participating.

But the story doesn’t end there.

Emotions continued to boil over as people lobbied hard to get the principal to change course and allow us to participate. I suspect the superintendent heard from a lot of people as well. Paraprofessionals and other non-faculty (secretaries, assistants, teaching assistants, cafeteria workers) complained that the decision had been made without them. And in those days following the vote, it became clear to anyone paying attention that most of the non-faculty were not on the same page as the majority of faculty who had voted during the meeting. Another sign of things to come.

Some people were seething and, hard as they tried to understand where others were coming from, they just didn’t get it. Neither did I.

It didn’t take long for students to pick up on the fact that something was going on—they kept seeing small groups of teachers and staff huddled together in the hallways talking, arguing and sometimes crying.

When one class asked me what was going on, I told them. I explained that the secretary of education had asked all schools to pause together on Friday, October 11th, to say the pledge of allegiance. I explained that when the principal had announced it, some faculty had strong objections. I told them that it had been put to a vote and those who opposed our participation won. I did my best to fairly and respectfully summarize the arguments of those opposed (without naming names, of course) and I shared with them my reasons for being upset with the decision.

One of the students, who went on to join the Marines, had a strong reaction and made an important point that hadn’t even occurred to me.

He was angry and aggrieved over the fact that his teachers had taken away the opportunity to participate with the rest of the country without even asking him and his fellow students what they thought. He was bothered by the fact that he and the rest of the students wouldn’t have even known the rest of the country was doing the pledge together on Friday if I hadn’t told them.

Remember, this was 2001 and there was no Tik Tok or Snapchator Instagram to spread the word about a nationwide event happening in schools.

The principal spent the next 24 hours fielding nonstop phone calls, emails and visits to her office from people who wanted to share their thoughts and make their case. Local tv and radio stations reached out for comment as word spread that Wellesley’s teachers had voted not to do the pledge with the rest of the country on Friday, October 11th.

Relationships within the building were strained, even fractured for a time. Long emails were exchanged as colleagues and friends tried to understand one another and be better understood. Paraprofessionals were confident that the vote would have gone differently if they had been included—I agreed with them. Those with loved ones who worked in police and fire departments were especially angry. And hurt.

The biggest sticking point for me—that had me choked up a lot during these conversations in the hallways— was the fact that every first responder who ran into those buildings had worn an American flag on their arm. That the bodies being carried out of the rubble were draped with the American flag. That those putting their lives at risk to be part of the rescue and recovery efforts wore the flag, our flag. I explained this to those who disagreed with me and while they said they understood and respected my point of view, they “just didn’t see it that way.” Meanwhile, I was floored that so many of my colleagues, people I respected in so many ways, were unable or unwilling to put aside their own personal baggage even for 2 minutes to be part of something larger than themselves.

In the end, the principal changed course and went with a compromise. The school would pause what we were doing Friday at 2:00 and classes could choose what to do—most pledged the flag, some sang God Bless America and the national anthem, others just talked about their thoughts and feelings about everything. Maybe some did all three. I didn’t have a class that period so I went to a nearby classroom of seniors to say the pledge with them.

I realize now that during that meeting the first week of October in 2001, I, as a young teacher in one of the wealthiest school districts in America, got an early taste of the anti-American, anti-western worldview and “inclusion” madness that would come to capture so many schools in the future. No wonder I felt so sick over it at the time.

Every year on September 11th, I think back to this heated debate that blew up at a faculty meeting less than a month after the twin towers had fallen and our country was forever changed. I have wanted to tell the story for a long time.

Now I have.

Thank you for sharing your story. It is often these wealthy, over "educated" narcissistic people who don't realize how good they have it. They don't realize how wonderful our country is. They are ungrateful. They have too easy of a life, without any real problems, which causes ingratitude. They cannot express gratitude for the freedoms of this country.

My husband and I both immigrated to the USA from Europe, as kids, and we are very patriotic. Yes, we have experience Plenty of Anti Semitism, both here & all over the world, but it has nothing to do with this wonderful country, but rather has to do with the existence of people who are racist & bigoted, which is in all countries. We live in a wealthy neighborhood. I am very conscious of making sure my 3 kids express gratitude, on a regular basis. We do teach them patriotism. We teach them to be grateful for what they have. I do allow them to experience problems & hardships. I don't helicopter parent or "protect" them from life's problems/consequences, because the more problems and hardships one faces, the stronger a person becomes, through adversity. One learns resilience.

Great article. It’s sad how this has become such a decisive issue today. My dad was so proud the day he became a citizen and he was grateful that in America a man can come over on a scholarship with an apple, rice cooker and $20 bucks and die a millionaire. Sometimes we forget that the freedoms we have come at the cost of many brave men and women who serve and the flag is a symbol of that freedom.